A Brief but Complete Guide to Guitar Compression

Compression is one of the most confusing effects to incorporate into your guitar chain. It’s a misunderstood effect.

What a compressor actually does isn’t all that confusing. The difficulty is in its application.

Let’s start at the beginning. A compressor’s purpose is to even out your guitar’s signal. With a clean guitar, you will see peaks in the recorded sound. Lots of peaks and valleys. The transients pop out. The difference between those peaks and valleys could sound jarring or cause overload, depending on what you’re running your signal into.

Compressors were invented to reduce the distance between peaks and valleys. This allows for a more consistent sound and has benefits like preventing tape output from overloading and digital output from clipping.

Clean guitar sounds have a lot of dynamics. Compared to the piano, which has fairly even dynamics, the guitar has a quick transient with relatively short sustain. Guitars are very transient-heavy instruments.

This is simply the nature of guitars. I’m not talking about uneven dynamics in playing. I’m talking about the natural, wide dynamics of the guitar.

Some use compressors to control the dynamics of guitarists who lack finesse. Yes, you could use a compressor this way, but I tend not to. I’ve spent a lot of time practicing in order to control my dynamics.

I believe compressors shouldn’t be used to fix poor playing dynamics, but to control the natural dynamics and shape the tone of the guitar.

So I’m going to focus here less on using compression to fix poor guitar playing and more on its influence on guitar tone.

Why compress?

Because the guitar has such a wide variance of dynamics—transients pop out, while softer parts are left in the wind in live mixes and recording.

Compression lets you glue the sound together. You can sometimes even out your tone through your playing, but because of the guitar’s tonal nature, you’ll never even out the sound the way you can with a compressor.

It’s very common for guitarists to use compression with super-clean acoustic and electric guitars. Compression on a clean guitar sits better in the mix. You don’t get those notes or chords popping out.

This doesn’t mean I run to a compressor for every clean sound.

The quiz

A decision must be made before adding compression: Should you add it before or after the guitar amp?

A compressor’s placement in the electric guitar signal chain affects the shape of your tone. In a live setting you have fewer options. But in a recording studio you can place a compressor before your amp or after the microphones.

Let’s talk about scenarios

Before the amp:

When I’m playing slide guitar I like to have a compressor before the amp. This is not a hard-and-fast rule; other elements may change my decision. What amp I’m using, how loud the amp is, what guitar I’m using, what other pedals I’m using all influence my decision.

That said, I do like the Origin Effects SlideRIG for clean to semi-clean slide electric guitar. This always goes first in my signal chain, before the guitar amp input.

I also like to use an Analog Man CompROSSor pedal with my Rickenbacker 360 12-string for Byrds and Tom Petty tones. The CompRESSor also goes before my amp input.

I sometimes use an Effectrode PC-2A on rhythm guitar for semi overdriven tones or to create a tube sag effect when playing at low volumes.

For semi-overdriven tones I place the PC-2A before my drive pedals or amp. For a tube sag effect, I place it after the overdrive pedal to duck the signal slightly when I hit it hard. Sounds just like some tube amps do when fully cranked.

Each of these compressors change the way I interact with the amp. It’s also possible to use compressors to change the gain staging with the amp.

Placing a compressor before the amp also allows me to adjust how much volume I’m hitting the front end of the amp with. If I want, I could add a little gain to push the amp into saturation.

Other uses for a compressor

Sustain

Some guitarists like to use compression before an overdrive pedal to add more sustain to their guitar solos. You can use a compressor before a drive pedal a few ways:

1: A compressor before an OD pedal with no added output gain can add sustain.

2: A compressor before an OD pedal or overdriven amp with additional output gain can drive the pedal or amp harder and add sustain during the solo.

3: A compressor before an OD pedal or overdriven amp plus a minimal amount of compression but lots of output gain can push the amp or OD pedal harder.

You can achieve a similar result cascading OD pedals or using a boost pedal before the OD or amp. Each method sounds slightly different. It’s worth experimenting to hear what works for you.

Some of my fave combos for this purpose are using an Analog Man CompROSSor or Effectrode PC-2A before a Effectrode Tube Drive or JHS Bonsai.

A little goes a long way

When using pedal compressors, be mindful not to add too much compression. It always feels good to add more compression, but at stage volumes or in playback you’ll quickly notice issues.

Too much compression can dull your sound. It can also make your sound too small and contained. We’re usually just looking to reduce the distance between the peaks and valleys. We don’t want to turn it into the flatlands. Compression tends to be trickier with guitar pedals, as they don’t have meters. Studio compressors have VU meters that let you see how much compression is being added.

Unless I’m specifically going for a special effect, I only compress by a few dB. Exceptions here are with the SlideRIG when I’m playing slide, the CompRESSor for my Rickenbacker, and the Orange Squeezer for country chicken picking. Or if I just want a squashed effect.

It takes a long time to really hear the subtly in compression. Until you get here, always compare to compressed and uncompressed sounds.

Post guitar and amp compression

A lot of times in the studio I’ll use compressors after the guitar or guitar amp. These post-guitar placements are well suited for such goals as reducing the distance between peaks and valleys. (I keep mentioning this because it’s important to visualize.)

I also use compressors when recording for their tonal character just as much if not more than for dynamics control. For many decades, recording engineers and mixers have used analog hardware compressors to color guitar tones.

Some of the classics used for this purpose are the Fairchild 660, the Urei 1176, the Teletronix LA-2A, the UA 175b and 176, the Empirical Labs Distressor, and the LA-3A, just to name a few. The emulated analog circuitry in each of these compressors is unique.

On the subject of analog compression, I still prefer to use an analog compressor for recording guitars before my converters. To my ears, it just sounds better than adding compression later on.

My favorite analog compressor for this purpose is the Purple Audio MC77 compressor. The MC77 is an updated UREI 1176 Revision E circuit with a lower noise floor and improved reliability. The MC77 also allows you to run through the circuitry without compression. More on that later.

Converted

I always use the Purple Audio MC77 when recording acoustic guitars as well. Personally, I prefer access to a bit of compression before the converters when recording acoustic instruments in the digital realm. In the olden days, your signal was going to tape, which had a slight amount of natural compression. So to make up for that deficit in the digital world, I compress on the way in a touch.

Tube compression

The Fairchild 660, Teletronix LA-2A, and UA 175b/176 compressors are all tube compressors. Guitarists more than any other instrumentalists should immediately appreciate the value of tubes to sonic identity.

Tubes can add harmonic complexity and distortion. Sound familiar to all you amp nerds? Using a Fairchild, Teletronix LA-2A, or UA 175b/176 and not adding much if any compression immediately adds character to your signal.

Some compressors even allow you to run through their circuitry without adding the compression. The UA 175b and 176 compressors include the option of keeping the I/O amplifiers active while turning off the compression.

The same can be achieved in the analog world on the Purple Audio MC77. When you turn the Attack knob fully counter-clockwise, it disables the compressor from engaging. But, you still get the sonic goodies from the MC77 circuit.

This tube sound of the 175b/176 and LA-2A are quite different from the solid state sound of the 1176 and LA3A. The 1176 has its own unique way of adding overdrive with a “fast attack and release” setting.

I don’t think about doing this with just outboard studio compressors. I do it with pedal compressors. The Effectrode PC-2A is a tube compression pedal based on the LA-2A circuit. The Origin Effects Sliderig is based on the Urei 1176 circuit.

In addition to deciding which one will be better at compressing a certain source, I’m also thinking about the tone each one adds. I may even use the Analog Man CompROSSor for slide because of the sonic imprint it adds. There are no rules. You just have to get familiar with the tone of each compressor and apply accordingly.

Side chain

One feature that hasn’t existed on guitar pedals is the ability to adjust how much low end gets compressed in the guitar signal. Universal Audio has added some great features on top of its meticulously modeled classic compressors.

On its UAD LA-2A, Distressor, and Fairchild compressors, Universal Audio offers the option of adjusting low end compression. This is handy when the low end is causing the compressor to pump too much.

On the LA-2A this adjustment is called “emphasis.” On the Farichild and Distressor it’s called “sidechain.” I have found both handy when dealing with heavy compression on guitars with too much low end content. Sometimes I really like the pumping compression tone. Other times I want it to be squashed with less low end pumping.

How much compression?

“Unless I’m specifically going for a special effect, I only compress by a few dB. ”

Most of the time I’m only compressing a few dB, often no more than 3bB. I do like the sound of a heavily compressed acoustic guitar. But this tends to fall into the “compression as an effect” category.

I ask myself four questions (in no specific order) when adding compression to acoustic or electric guitar.

1: Am I looking to add the character of a specific compressor?

2: Am I looking to even out the peaks and valleys?

3: Am I looking for a special compressor effect?

4: Does the compressor need to interact with the front end of the amp or the performance?

Question 4 implies that I need to be thinking about compression pretty early on in the guitar tone decision process. As soon as I start working out a part for a gig or recording, I envision the tone I want and consider what tools I’ll need to create it.

As you can see, using compression isn’t just about fixing dynamics.

Apples to Apples

One point worth noting is that plugin compressors and analog compressors don't operate the same even if the plugins have been modeled after the same circuit. I can be more aggressive with the Purple Audio MC77 than I could with an 1176 plugin. A hardware compressor is more forgiving.

For this reason, a lot of mixing engineers use compression plugins in series. By placing one compressor plugin after another and pushing each one less, you will hear the compression less. I often reach for my Purple Audio MC77 when tracking to allow more of a range of compression as I find it more "musical."

Attack and release

Attack and release knobs tend to really confuse a lot of guitarists. The first bit of advice I’ll give is to close your eyes and listen as you turn each knob. Envision going to the eye doctor where they put you in a dark room with a contraption in front of your eyes that has a variety of lenses.

While you look at a letter chart, the eye doctor switches the lenses and asks, “better or worse?” Every time I make an adjustment on a guitar amp, pedal, guitar, preamp, compressor, or mic, I ask myself “better or worse?” Sometimes I don't even care what I adjusted. I just care if it improves the tone.

“Every time I make an adjustment on a guitar amp, pedal, guitar, preamp, compressor, or mic, I ask myself “better or worse?””

A lot of guitarists get caught up in trying to research the optimal attack and release times for acoustic, electric guitar, and bass. I find it’s more important to use your ears. You have to spend time tweaking to really hear how the attack and release knobs change the sound.

Attack adjusts the amount of time it takes the compressor to grab the signal. The slower the attack, the more signal is allowed to pass before it’s compressed.

The faster the attack the time, the quicker the compressor grabs the signal and compresses it.

The release knob adjusts the time it takes for the compressor to let go of the signal. The faster the release, the quicker your signal is restored to its original state. The slower the release, the longer the compressor will hang onto the signal.

Neither control is difficult to understand. But if you make your decisions simply on this knowledge, without listening, you’re missing out. You might be surprised where these knobs sound best.

Rule of thumb: the faster the attack time the quicker it will contain peaking transients. So if you’re trying to stop transients from popping out, a fast attack time will be best.

Threshold

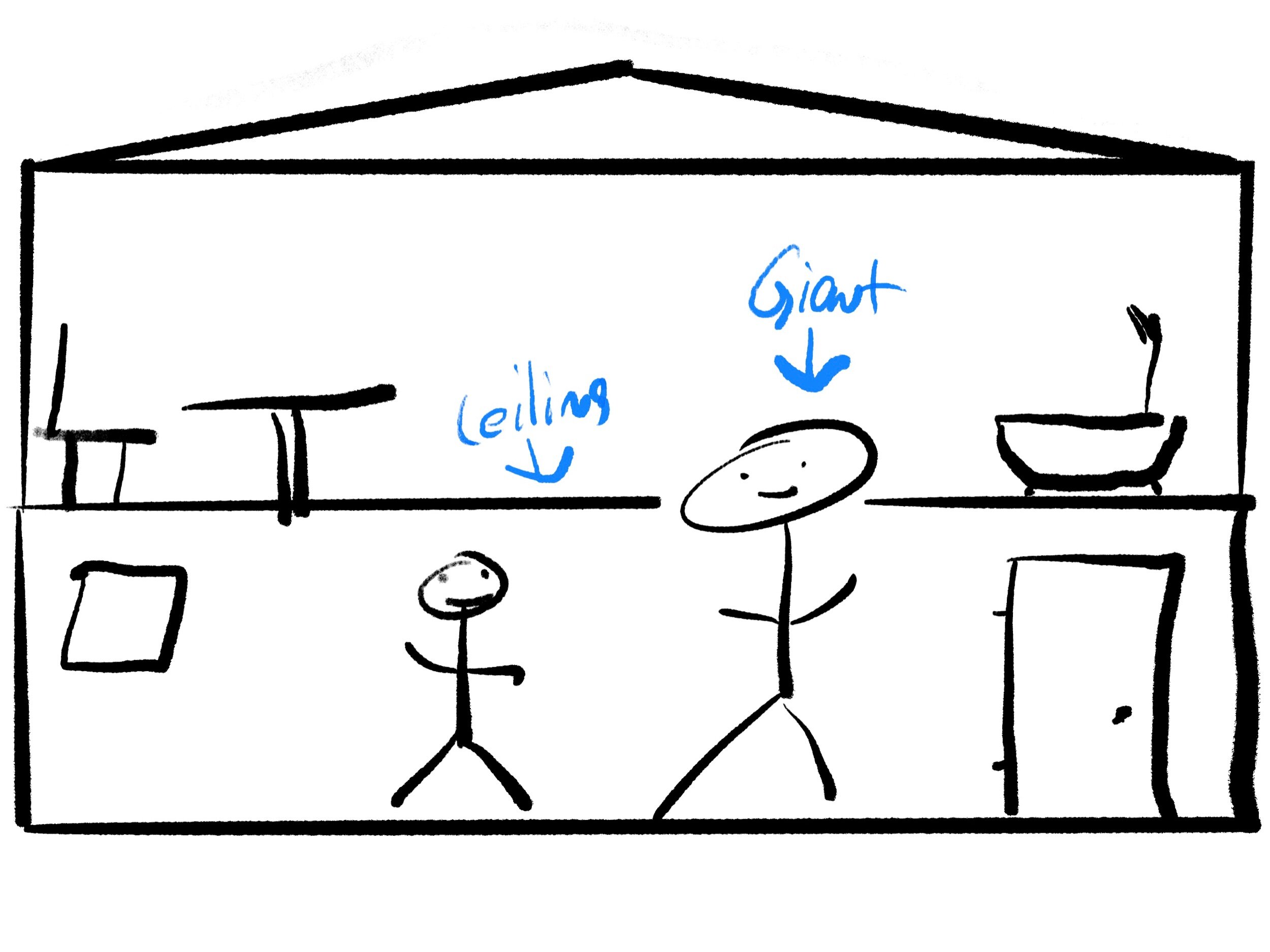

Think of threshold as a ceiling. Imagine an 8-foot giant walking into a room with a 6-foot ceiling. The giant has to duck down to enter. The threshold setting on a compressor sets the ceiling. The lower the threshold, the sooner the signal will compress. In other words you’re lowering the ceiling on the giant and making it hunch over more.

The threshold sets the level where compression starts.

Ratio

Going back to our giant in the room, I think of ratio as the material the ceiling is made of. Imagine the ceiling is made of foam. As the ceiling gets lower, there’s some flexibility when it reaches our giant’s head. If the ceiling is wood, there’s no flexibility.

The lower the ratio, the more gentle the ceiling is. 2:1 compression is a very soft foam ceiling. A 20:1 ratio is like concrete— zero flexibility.

Ratio determines how gentle the compression is as it passes the threshold. It’s good to understand this concept. It’s even better to experiment and listen to the results. Trust your ears.

Some compressors such as the LA-2A have a switch to alternate between compression and limiting. The only difference between limiting and compression is the ratio. When engaging the limiting switch, it applies a higher ratio to the circuit.

You can use the limiting function when you want to clamp down on a signal from exceeding the threshold.

Other compressors such as the Distressor have as an option for a 20:1 ratio or nuke. A ratio this high is going to result in brick-wall limiting. Meaning nothing will exceed the threshold.

Brickwall limiting is used in mastering, but can also be handy in mixing if you need to batten the hatches on a signal.

Gain staging

It’s been said too many times that signal doesn’t matter in digital. You can record quiet signals and level up later. Well, this isn’t entirely true. The analog-emulating gear by UA and Waves fully emulate those hardware devices. This includes the noise floor of the real hardware.

This means if you send too low a signal into a modeled UA compressor and then use the input knob to get the level up to where it starts to compress, you will raise the noise floor.

It’s better to record a signal the compressor likes to see and then use the input knob if you want to push the sound more into compression.

Th UA compressor plugins operate at -18dB = 0dB. This mean that a reading of -18dB on a VU meter will actually be 0dB.

They key here is to record your guitar signal so the peaks reach -18dB on a VU meter. Anything over 0dB is the level where most compressors will start to compress, unless they have a threshold knob.

I record my guitar signal to peak at -18dB and then use the input knob on the compressor (if it has one, like the 1176) to push the signal further into compression.

This keeps the noise floor down and allows the compressor to operate as expected. I see a lot of guitarists perform inconsistently with compressors because their recording signals are all over the place.

I’m always watching my meters! Gain staging is one of the most important details of recording.

Blend knob

Another cool feature about the plugin compressors from Universal Audio or Waves is that they’ll sometimes give you a blend or mix knob which doesn’t exist in the hardware world.

A blend/mix knob allow us to achieve parallel compression without complicated routing.

The mix/blend knob allows you to mix or blend in the clean uncompressed tone with the compressed tone. I find myself using this feature a lot these days. I can dial in a heavier compression setting and then blend in clean sound to get some dynamics back.

Some pedals such as the Origin Effects SlideRIG have a mix knob which I use quite a bit as well.

Buyer beware

Not all compressors are created equal. I find this to be especially true with guitar pedal compressors. There are some I simply don’t like the tone of. It took me a long time to find some pedal compressors I really like. Same goes for studio compressors.

Don’t be fooled by the word “transparent.” Every compressor has a flavor. It just depends on your perception of what’s neutral.

Many so-called neutral or non-colored compressors sound lifeless and dull to my ears. For instance, the Wampler Ego compressor (which some love) sounds flat to me. It’s a very well made pedal but I just don't like the tone. Ditto for the Xotic SP compressor. A very convenient nano pedal but I just can’t roll with the tone.

I feel the same way about the stock compressors in Logic and Pro Tools.

None of this means you won’t like these compressors. It just means don’t buy into the “transparency” buzzword. I have the similar feeling about “transparency” as I have about pedal platform amps.

Takeaway

The more distortion a guitar has, the less likely I am to compress in order to tame the peaks and valleys. This is because heavy distorted and fuzz guitar tones are compressed by nature. If you look at a fuzz guitar waveform you won’t see many valleys.

Using a compressor to control the dynamics on a distorted or fuzz guitar isn’t necessary. But it doesn’t mean I don't use a compressor to color the tone. I may use a Urei 1176 style circuit to add color with no compression. The Purple Audio MC77 is perfect for this purpose.

Adding an MC77 to a gainy guitar can fatten it up and tame some of the shrillness. If you're using a compressor that doesn't have the option to disengage the compressor, watch those meters. The idea is to add color—not compression!

And remember, compression doesn't have to happen at one point in the chain. For example, I often use a pedal compressor to get a little squeeze before the amp, such as the Analog Man CompROSSor, and then a Purple Audio MC77 after the amp before the converters.

I hope this discussion demystifies compression for you. I think it’s important to research the sounds you like. Different genres of music and guitar playing styles use compression in different ways.